There used to be a Tower Video store near the corner of Market and Noe Streets. I loved dropping in on the way home from work on Friday nights. Sometimes renting DVDs, but more and more often buying them as prices dropped. In the weeks just before Tower closed their doors for good they had big bins of DVDs in the front of the store near the windows, and you could buy two or even three DVDs for just a few bucks. I began picking up armfuls of noirs, mysteries and classic horror movies – genres with a high melodrama quotient. And almost all the prints were in glorious black and white.

I’d stroll out of Tower carrying a bulging yellow bag or two, stop by la Mediterranee for take out of whatever amazing chicken special was offered that evening, then hurry home to lay the swag before my wife. We usually ate dinner while watching whichever of the movies I’d brought home she thought she’d like best…or mind least…then I’d put on the earphones and watch three or four more until I simply couldn’t keep my eyes open any longer.

It was during one of these late night movie binges that I discover a 1951 RKO Pictures production called “His Kind of Woman.” It was included in a film noir collection, and it certainly has the look of a noir. But it’s also wildly comical. And there’s something wonderfully fresh about its hero in terms of what he confronts, how he responds, and the liberties he achieves as a consequence. Also, as I learned about the strange circumstances under which the film got made, I came to think of it as an extraordinarily willful act of self expression on the part of its producer, Howard Hughes.

Hughes acquired the RKO Studio in 1948. Over the course of the next eight years he destroyed it. His opening move was dismissal of three-fourths of the studio’s employees. As the craziness that became known as McCarthyism gained traction, he did not try to shield the studio’s talent from the purge. Rather, he enthusiastically tossed suspected Communist sympathizers off the payroll. And from first to last, his imperious micromanagement undermined his creative teams’ control over their work. Lots of theories have been offered to explain why he would do so many things that could not help but gut the studio. For example, some contend that RKO was already losing money before Hughes took the helm, and because he really didn’t understand the movie biz, he did things he hoped would cut costs that actually hurt the business more.

My guess is he never really cared about the studio as such. Acquiring RKO was just a convenient way to get all the things he needed to create self portraits on a scale as big as the technology of the time permitted. Projected patterns of light on huge silver screens that brazenly offered for examination everything he knew about everything. Images of his world view and inner self that would live on long after he was gone. When it came down to it, such a project really didn’t need a whole Hollywood studio. And it certainly didn’t need other people with other visions trying to interject their stuff. He wasn’t in it for the money, or to provide employment for others. It was self portraiture in a medium only a Titan could afford. RKO Pictures was his pantry of consumable art supplies.

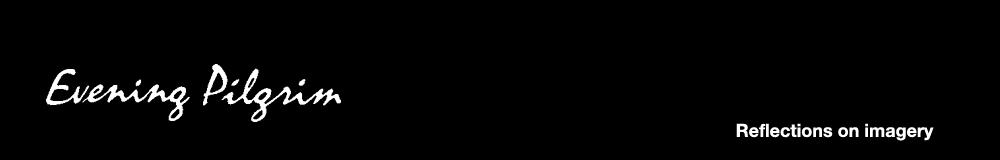

Concerning “His Kind of Woman”, I mentioned finding something wonderfully fresh about what its hero confronts. He’s a loaner, a gambler, and smart enough to understand that the less people know about you the less control they have over you. But those qualities also combine to make the hero the perfect victim for a bizarre crime – identity theft. Not to acquire what he has, but literally to become who he is. At its core, the story is about a guy threatened with complete obliteration by a powerful, evil force that wants his face.

To illustrate how the hero responds, and the liberties he achieves as a consequence, let’s travel in our imaginations to Jamaica. It’s 1952, a balmy November afternoon in Kingston. Former British Intelligence Officer Ian Fleming is thinking he’ll catch a matinee at the Carib Theater, then perhaps dine in town before driving back to Goldeneye, his cottage on the northern coast of the island.

“Always nice to see a local girl make something of herself,” he muses, admiring Jane Russell’s extraordinary form cozy in Robert Mitchum’s arms above the matter-of-fact statement in large block letters, “His Kind of Woman.” When visiting Jamacia the actress often dined just down the road from Fleming’s house at the Casa Maria Hotel where he spent the occasional evening drinking with friends. It would be downright un-neighborly to let one of her movies come and go without dropping a penny in the till.

Now fast forward two hours. Fleming emerges from the theater and hastens to the bar across the street where he scribbles notes on napkins until his pen runs out of ink. The camera moves in close on a sentence or two.

“The personification of evil is a creepy, sociopathic international crime boss who can afford the best high-tech toys.”

“The bad guys can afford layer upon layer of opulent deceit and obfuscation.”

“The hero cleans up good and displays effortless cool in the best and worst company.”

“His pal is a generous, brave, loyal, heavily-armed American gifted with more wealth than brains.”

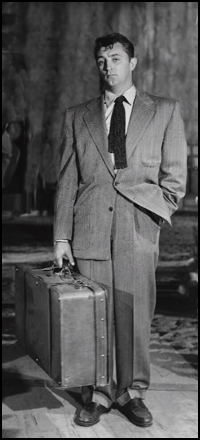

“There’s a mad scientist with monstrous plans.”

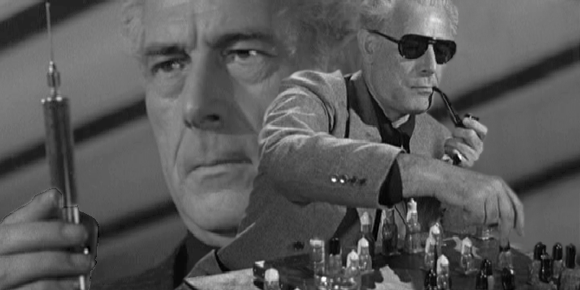

“The hero endures extraordinary brutality…”

“…but lives to woo another day!”

We see Fleming at his desk typing furiously. The surf rolls in off the Caribbean to splash on glistening sands in the background. A tropical breeze rustles the calendar, the days begin to fly away and in an instant two months have passed. Fleming pulls a page from the typewriter, lays it on a large stack of paper and turns the manuscript over. The title reads, “Casino Royale.” By March of 1953 the first James Bond novel is in print and selling briskly in Britain.

It is not known if Fleming and Hughes ever met, but Hughes’ dear friend Cubby Broccoli brought the James Bond films to the big screen. Broccoli had met Hughes while working as a gofer on the Hughes 1941 production “The Outlaw” starring Janes Russell, and they remained lifelong friends.

PS: “Continuity of motion” is a motion picture editing term referring to the flow of action from one shot to the next as it is placed on the screen at the cut point. Placing the significant action at the end of a shot in the same area of the screen where the significant action will begin in the next shot.