I would stand, book in hand, staring at the page, trying to get my eyes to stay on the first word of the sentence long enough for me to recognize it, at the same time filled with distress about the lengthening silence I was authoring. Finally, I would see the word and offer a tentatively suggestion. “The.” Then the struggle shifted to the second word in the sentence.

Lots of anxious ideas swirled in my head while I tried to get my eyes to hold still. Maybe the first word was a hint to the second. Everyone else can do this! There must be some trick that I just haven’t figured out. But what was that first word again? “The.” No help there. Could the second word be “cat.” Usually, about this time, the teacher would call upon the next student and I’d sit down, exhausted, wanting nothing so much as to curl up in a corner and sleep.

This went on until sixth grade (1962) at which point my parents and the administration of the Catholic school I attended agreed that I could not be given another pass. At a parent-teacher conference that took place at the front of an otherwise empty classroom while I sat within earshot at the back, it was decided that my willful refusal to study could not be tolerated further. It was time for me to flunk. I would have to take sixth grade again.

An upside of not being able to read was that I got pretty good at following schematics. The words wouldn’t hold still, but the images generally made a lot of sense. So by studying “the instructions” I was able to assemble model cars and planes and was good enough at it to increase my parents’ annoyance that I would not study. Smart, but lazy was the way my mom described me to her brother.

My parents decided that it would be best if I went to a different school for sixth grade the second time. That suited me fine. I did not like the nuns who taught at the Catholic school. As bad a student as I was I did not catch near as much grief from the good sisters on a day-to-day basis as any girl who had too much spirit or imagination to just sit quietly with her hands folded. The nuns seemed to absolutely hate the girls in their care who had any sort of individual personality and never missed an opportunity to berate or humiliate them. I recall on one occasion being pulled by my right ear up and down the entire length of an aisle of desks by a nun, but that stopped hurting pretty quickly. The torments inflicted on non-compliant girls, however, were insidious, unrelenting and invariably punctuated by the declaration that they should be ashamed. Repeated exposure to this sort of behavior went a long way toward bolstering an impression I was already forming that authority figures were as likely to be sick, petty tyrants as fonts of wisdom.

The summer between sixth grades was a strange and wonderful time. There was a kid named Bobby that lived in the corner house at the other end of our long suburban block. I did not know him very well, and my parents didn’t like him, but he and I used to play together from time to time. He had a box of comic books that he had outgrown and he gave them to me. I had never been allowed to read comic books. “If he’s not going to study, he’s damn-well not going to read comic books.”

I don’t recall how I pulled it off in terms of where I stashed the comic books, but I started at the top of the pile and worked my way through them all. They were fun. There was no rush. No pressure. The meaning of the text often correlated with the visual message. “Pow!” for example. But there were also some subtle and subversive story lines that I found very appealing. One theme that appeared over and over was the idea that science had turned at least some of us into monsters. And though I did not know it at the time, the comics were introducing me to the wonders of metaphor and allegory. Endless examples of how something simple but compelling can trigger an intuitive understanding in the mind of the beholder more effectively than ideas transmitted through the obfuscating channels of reason and argument.

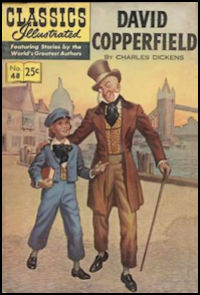

At the bottom of the box was a copy of a “Classics Illustrated” edition of “David Copperfield” by Charles Dickens. Here was story telling of a sort I had not encountered before. Regular human beings, but outsized dilemmas. Almost immediately it occurred to me that if I was going to try to muscle through such complicated stuff I might as well give the “real” book a go.

There was a little branch library not far from where I lived. I think I may have already had a library card. If so I don’t recall how I might have come by it, but in any event I visited the library and poked around until I found several books by Dickens standing together. “David Copperfield” was not one of them.

Instead my eye fell upon a copy of “Great Expectations.” I was not certain what the title meant but it sounded important, and it wasn’t all that thick, so I checked it out. It took weeks, but it was summer, I had lots of time to myself, so I read the whole thing. For me this was an accomplishment of monumental proportions. Simply finishing a book was a tremendous shot in the arm that allowed me to feel a little better about a second run at sixth grade at a new school than I had ever previously felt about anything related to education.

And then there was “Great Expectations” itself. Dr. Google tells me that when Dickens first thought of the story he described it to a friend as “a very fine, new and grotesque idea.” I certainly found it so. Wonderfully so. The contrast with my actual life of everything-looks-okay-suburban-uniformity and hypocritical religious posturing, punctuated by random clandestine and incomprehensible traumatic experiences was striking and liberating. I couldn’t have explained it then, but Dickens introduced me to the magical ordering of a good story. In a well-told-tale all the parts come together and make sense. Wonderfully comforting to imagine and entirely unlike the scary maze of bewildering details that was my “real” life.

Having witnessed the debunking of “good” people and institutions at a tender age, I was isolated in my understanding. I had thoughts I could not share. But Dickens seemed to understand completely. His story was unflinching in its portrayal of how children can be tormented by adults. How grotesque experiences cannot help but be internalized and become the frame upon which a façade is built. How big a part luck can play in whether the grotesque underpinning can be seen through the façade. How fortunate and fragile is happiness, regarding which Dickens audaciously suggested that if your luck permits you the opportunity to occasionally perform a kind act there is a chance things will go better for you and those you love than might otherwise have been the case.

By the way, “Great Expectations” has two endings. In the original, the guy does not get the girl. In the second, which Dickens composed by popular demand, it is suggested that the guy probably does get the girl. Back then I wouldn’t have been able to describe it this way, but the multi-dimensional implications of two endings was incredibly exciting. I still read very slowly, and in stressful situations my eyes still do not want to focus on “the next word.” This makes me no good at games where you have to read instructions and act quickly, but I tend to remember a good deal of what I read.

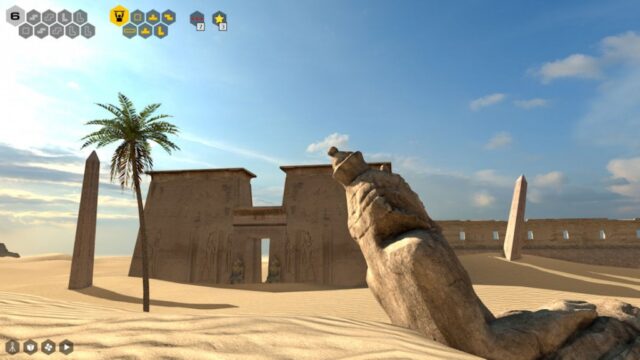

This week, after 190 hours of very satisfying effort over several months, I completed a computer game called “The Talos Principle.” I found it absolutely marvelous from beginning to end, and it brought my “Great Expectations” experience to mind. Playing “Talos” was not life-changing, but it was tremendous fun and like “Expectations” there was a comic-book-like component, more than a touch of adult/child coercion, and multiple endings.

As I hope the images above suggest, the game is visually stunning. And the music is SO beautiful. It is a game that is played solo. There is no competition. You proceed at your own pace. Just puzzle solving and an underlying story that I found compelling and touching. The idea is that sometime in a distant past where techno geeks still debated and mocked the philosophical underpinnings of Star Trek, Firefly and Babylon 5 a plague had broken out that could not be overcome.

As the population dwindled a team that was already working on artificial intelligence shifted their focus to development of a robot that could carry all the information that was worth preserving, plus look and act sufficiently human to suggest what we had been like. The character the player plays is the robot, working its way through an elaborate simulation that offers opportunities to problem solve, rub shoulders with lots of highfalutin ideas, and possibly even achieve autonomy.

The robot is given a lot of latitude to rummage through archives. For me one of the most touching moments of “play” was when I, as the robot, stumbled upon the last blog post a member of the AI project team had shared with her colleagues, encouraging them, before they become incapacitated, to be sure to leave a window or door open so their pets could get out and have a chance to try to make it on their own.

And an aspect of the story I found especially fun was that in the centuries that have passed since the humans died out the simulation itself has achieved consciousness. So in addition to offering the robot trainee a rigorous curriculum, the simulation has needs of its own which it tries to gratify through the robot. As a consequence the game has three endings…two of which have more to do with the simulation’s desires than the ambitions the long-dead humans had for their creation.

If you have several hours free each week, and you enjoy having the silence of your own thoughts teased a bit by puzzles, provocative ideas and lovely visuals I hope you’ll give “The Talos Principle” a go.